Once upon a time (i.e. in the 7th Century), there lived an Anglo-Saxon fellow called Caedmon, who one day decided to play with words in order to praise his God. Finding he liked the sounds of his little creation, he orally passed it on to his friends and family, who also liked it and told all their friends and family. A few decades later, another fellow called Bede ended up liking Caedmon’s Hymn so much that he decided to write it down. And so, one of the earliest recorded poems in the English language was, well, recorded.

Of course, the English they wrote and spoke back then was a completely different language from what we know and understand now. In fact, that language has a name of its own: Old English. (Yes, it’s a very original name, but trust me, when we say that Old English is old, we mean old.) Contrary to popular belief, Old English is not Shakespearean English—in fact, if you read or heard Old English, you’d probably stand/sit in shock for a few moments, then scramble for the Shakespeare because at least you’ll have a chance with him. Anyway, Old English was used from the 5th to 11th Century, before it evolved into Middle English (12th to 15th Century; and still not Shakespearean!), Early Modern English (15th to mid-17th Century; yup, and that’s where we find good ol’ Will), and finally, Modern English (mid-17th Century and beyond). But all this mini-timeline aside, I want to talk about “Caedmon’s Hymn” now because it was composed in English in one of its early stages, and because this makes it the very first piece of English literature that we have written down! Excitement for all!

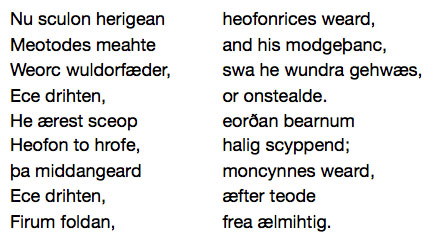

So let’s have a look at the poem itself (don’t worry, I’ve included a Modern English translation too):

And the translation!

Now we must praise heaven-kingdom’s Guardian,

The Measurer’s might and his mind-plans,

The work of the Glory-Father, when he of wonders of every one,

Eternal Lord, the beginning established.

He first created for men’s sons

Heaven as a roof, holy Creator;

The middle-earth mankind’s Guardian,

Eternal Lord, afterwards made –

For men on earth Master almighty.

And finally, a YouTube video of someone reciting the poem in its Old English glory!

Okay, so many of you have probably just read/listened to that and didn’t find anything spectacular about the poem and its translation, and may be thinking those are five minutes you’ll never get back…but keep in mind, this is the very first English poem, and there are actually quite a few funky things we can talk about! Now, I’m not an Old English/Anglo-Saxon/Medieval scholar, so I’m only going to talk about two pertinent points about “Caedmon’s Hymn” that majorly influenced poetry (in ways we’d probably never thought about before):

1. Rhythm

In my last post, I talked about Poetry and Metre (you might want to read that post and refresh your memory), and how I consider metre to be one of the defining features of poetry. I mentioned right at the end of that post that some poems don’t have a poetic metre, but a particular rhythm; in “Caedmon’s Hymn”, we don’t just have a poem with rhythm, but a poem with rhythm that is a precursor to metre as we now know it. Yup, without Caedmon, our concept of poetic metre today might be completely different!

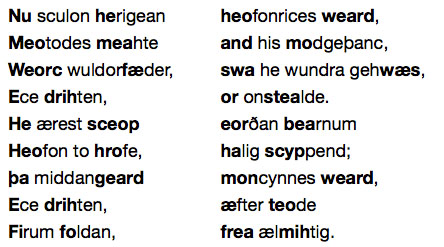

So, how is this rhythm constructed? Well, if we look at the original Old English version of the poem, we’ll see there’s an irregular number of syllables in each line (which makes it difficult for modern scanning). Instead of a specific order of stressed and unstressed syllables, here we have a particular number of stressed syllables amidst all the unstressed syllables, which in turn form a dominant pulse in each line. I know it’s difficult to imagine the sounds without knowing the language, so I’ve highlighted the stressed syllables for you (and you might also want to re-watch that YouTube video):

Did you notice there are four stressed syllables in each line? You may have also noticed the funky spaces I’ve put in each line—this isn’t just me wanting things to be pretty and neatly lined up, but is a literary device called the caesura, which is used to denote a definite pause in the middle of a line. If we think of the caesura as a break, and then take into account that there are two sets of stressed syllables in each line, and then look at the placement of the first stressed syllables, we’ll see there’s a definite pattern. In fact, what we have here is a sort of a trochee in each line—and, if we take it further, we can even say that “Caedmon’s Hymn” has a very loose, funky sort of trochaic tetrametre! Which brings me to my second point of:

2. Alliteration

Now, I’m sure most of you already know that alliteration is when we have a repetition of sound in the first syllables of words (and sometimes you can cheat by just looking at the first letters, except then I might catch you out with something like “the cool cat ceased the chase”). It’s become such a basic (and mostly easy-to-spot) literary technique that people don’t tend to wonder where alliteration came from—so this is where I tell you that alliteration originated in Old English and survived through poetry, and as “Caedmon’s Hymn” is both in Old English and the piece of earliest recorded English poem, we can conclude that Caedmon has played a very large part in bringing alliteration about! Of course, I’m not going to say that the fellow invented alliteration, or that he was the first to use it (because it would be rather silly and presumptuous of me to make claims about an oral tradition that took place over a thousand years ago), but there’s no doubt that “Caedmon’s Hymn” was quite influential in keeping the beat going. And speaking of beats, if you look back up to the poem, can you see how the alliteration is used to help with the stressed syllables in order to add cohesion and a sense of rhythm to the poem? Now that is the father of all English poems, that is history both preserved and evolving, and that is just really awesome.

And that’s all I have to say about “Caedmon’s Hymn”, one of the first pieces of literature that’s been written and recorded in the English language! Again, I’m not a medievalist, so if I’ve made any errors (glaring or otherwise), please correct me! Also, you may have noticed the lack of Wordless Wednesdays this past month, for which I apologise—I was absent-minded enough to misplace my camera, which has thankfully been found and is currently making its way back to me.

As always, please leave a comment to let me know your thoughts, your questions, your suggestions, your firstborn’s name… Until next time!

My firstborn’s name shall be Damien or Lily Elizabeth. Depending on whether said firstborn is a boy or girl, of course.

Yeah, I’ll be back to give a proper response to this awesome post when it’s not 2:30am on Christmas morning, lol.

Pingback: Daniel Defoe and His Novel Idea | Samantha Lin