Today, novels are found practically everywhere. One of my best friends, Sharyn (from Room 10), re-reads Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind every year. Another friend, Marissa Meyer, has recently seen the publication of her debut young adult novel, Cinder. Instead of writing this blog post, I should be making my way through Joseph Conrad’s Lord Jim for a class on Monday. We’ve gotten so used to the idea of the ‘novel’ that most of us assume the form’s been around since the beginning of time, when really, it’s existed for less than 300 years. A baby of a form considering its beginnings in English literature started 1,000 years after the writing of the first English poem, “Caedmon’s Hymn”.

The word ‘novel’ itself is a funny thing. Before it evolved into a noun that refers to the type of books we read today, it was (and still is) an adjective that means ‘new’ and ‘different from anything seen or known before’. And when it was first established in the 18th Century by a fellow called Daniel Defoe, the novel was certainly a novel thing.

Before Mr Defoe came along, stories were told in several other forms and genres such as narrative poetry (told in verse), drama (written with the intention of being performed on stage), and romances. This ‘romance’ isn’t the type of book with buff men and leggy women on the covers that we know today, but refers to a genre of prose that was predominant during the medieval period and told stories of knights, chivalry, and adventures at the Round Table. When the first novels came out in the early 18th Century, the good people of England had no idea what to do with this peculiar form that didn’t contain the elements of the material they were used to reading. And indeed, these novels are markedly different from romances, with its three key characteristics being:

- A protagonist who is not a hero by the traditional sense of a knight in faraway lands, but an ordinary individual to whom the audience can relate

- The narration of ordinary day-to-day events that don’t involve slaying monsters and dragons

- The use of a particular type of language that isn’t littered with extravagant similes and metaphors

In short, a novel contained a degree of Realism, which depicted ‘real’ and ‘realistic’ events as opposed to the extraordinary (well, events that were more realistic than wizards and sorcerers). And this is where Daniel Defoe comes in, with his two novels Robinson Crusoe (1719) and Moll Flanders (1722), which are considered to be among the first novels in English. Without spoiling the plot too much, let’s have a look at both novels and see how they fit those requirements.

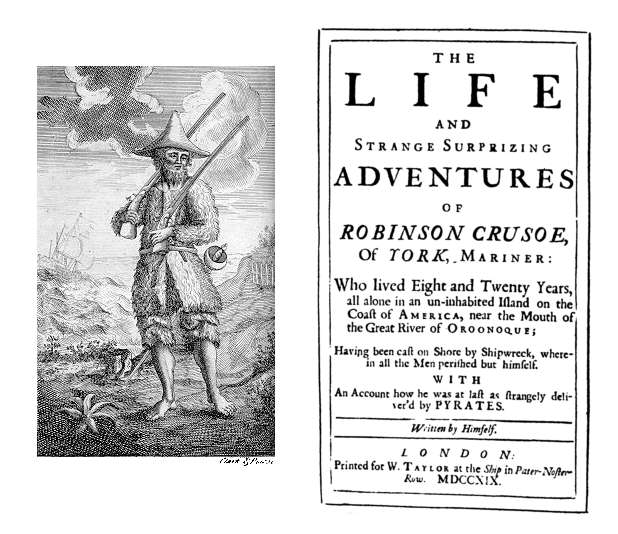

The Life and Strange Surprizing Adventures of Robinson Crusoe

Relatable protagonist? Mr Crusoe is a guy who rebels against his parents’ wishes for him to pursue a career and decides to set sail to a faraway land instead. Sounds like your typical emo boy.

Ordinary day-to-day events? Our dear, emo Robby is shipwrecked and ends up on an island, which probably isn’t considered ‘ordinary’. However, the narration of his adventures on said island is quite detailed and can be considered more or less ‘realistic’.

Non-flowery language? Let’s have a look at the first paragraph of the book:

I was born in the year 1632, in the city of York, of a good family, though not of that country, my father being a foreigner of Bremen, who settled first at Hull. He got a good estate by merchandise, and leaving off his trade, lived afterwards at York, from whence he had married my mother, whose relations were named Robinson, a very good family in that country, and from whom I was called Robinson Kreutznaer; but, by the usual corruption of words in England, we are now called—nay we call ourselves and write our name—Crusoe; and so my companions always called me.

Pretty straightforward, I’d say.

Two and a half ticks, and we’re good to go for one of the first novels in English!

The Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Famous Moll Flanders

Relatable protagonist? Miss Flanders (which isn’t her real name) is a young lady who, due to circumstances, grows up to become quite the con artist. Throughout her life, she forms relationships with several men, and has a couple of children—maybe a tad adventurous, but nothing too extraordinary or fantastical here.

Ordinary day-to-day events? The novel is littered with details of the daily proceedings in the life of Miss Flanders, to the extent where we get copious descriptions of the streets and clothing and how to swindle rich men. Overall, quite realistic.

Non-flowery language? Again, let’s have a look at the opening paragraph:

My true name is so well known in the records or registers at Newgate, and in the Old Bailey, and there are some things of such consequence still depending there, relating to my particular conduct, that it is not be expected I should set my name or the account of my family to this work; perhaps, after my death, it may be better known; at present it would not be proper, no not though a general pardon should be issued, even without exceptions and reserve of persons or crimes.

Non-flowery, I’d say.

And that’s three ticks, for another of the first novels in English!

Cover of the First Edition of Robinson Crusoe (1719)

Thanks to Danny boy and these two novels, a bunch of other folks decided to write in the same form. These people include: Eliza Haywood, authoress of Love in Excess (1720); Samuel Richardson, author of Pamela (1740) and Clarissa (1748); Henry Fielding, author of Joseph Andrews (1742) and Tom Jones (1749); Lawrence Sterne, author of Tristram Shandy (1759-1767); and John Cleland, author of the raunchy Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure (1748), which should definitely be kept away from the young’uns. All in all, the 18th Century was quite a productive year for the novel, considered at the time to be a new form of writing—a form that has certainly grown exponentially since!

(If you’d like to find out about the rise of the English novel in more detail, consider checking out Ian Watt’s The Rise of the Novel: Studies in Defoe, Richardson and Fielding. You can also find the full texts of Robinson Crusoe, Moll Flanders, and all those other novels on Project Gutenberg.)

Questions? Thoughts? Favourite novel? Your initial guess as to when the first novel was written? Fire away in the comments!

What scares me is I’ve read Defoe, Richardson, and Fielding AND I’ve read Ian Watt’s The Rise of the Novel. It’s almost like I’m an English major! Except not…

lol, I’ve read them all too! Though, I am an English major, so… :D

Heehee! You do realise the only thing I was thinking about during this blog post was Bill Walker’s lectures on the same subject? Though I’m sure you knew that already. :D